This is something that I wanted to start doing a year ago. I even downloaded a couple of issues during the summer, but I didn't get around to reading them. PDF files take up a lot of room, so I usually read them on my PC.

Why 50 years ago? There are a couple reasons that come to mind. First, I had a discussion online a couple years back saying that they could find good science-fiction stories for anthology shows on streaming platforms if they just went back to these old magazines. Yes, some are dated, and the ones with bad Science can be skipped over. Yes, some may not hold up to today's sensibilities, but, again, some of these might be rewritten with better characers and dialogue. I'm thinking about the main story ideas, not a wholesale adaptation.

Funnily enough, the title of the editorial by John W. Campbell is "The Baby in the Bath Water". That's pretty much the main idea of the previous paragaph. Dump out the dirty bath water, but keep the clean baby and nurture it.

In this issue:

The Editorial: In "The Baby in the Bath Water", John W. Campbell essentially rails against the cancel culture of the 70s. The mindset is that the Baby has been contaminated by the dirty Bath Water, so it must be gotten rid of. In particular, people (especially college students) want to shut down military-funded research. He goes on at length providing examples, military or otherwise, why this would be a bad idea. It can be extrapolated for today's banish and boycott world. I appreciate the argument he makes.

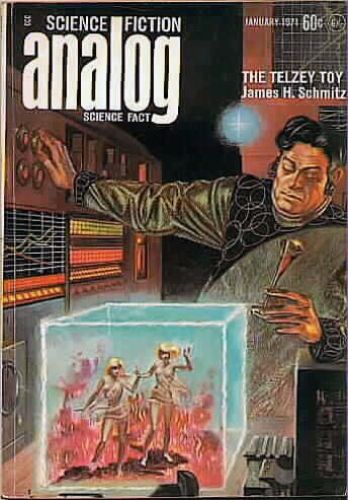

Novelette: "The Telzey Toy", by James H. Schmitz, with an illustration by Kelly Freas of two women tied like marionettes, being watched by a man wearing a dome-shaped hat with a spire, sitting in a chair by a control panel. The caption reads: It wasn't so that Telzey bit off more than she could chew -- but that somebody took her teeth away!

This is also the cover story. The cover shows a large man, no hat, with one hand to a full wall panel of dials and counters, while holding what appears to be a glass of wine. He's observing a holocube, which displays two women, blondes in translucent clothing, running through a field. The colors are distorted. This is the more realistic of the two illustrations, with the other being symbollic. That said, while it's implied that he has ways of keeping tabs on the women, I don't remember mention of any 3-D viewing device.

The story opens in Orado City, where Telzey, a psi, spots a familiar-looking woman. She realizes that she resembles a player in a Matri-drama. Matri are a kind of near-human marionette, with limited functionability. One shouldn't be able to walk around in public unattended. Telzey uses her psi abilities to read the Matri's mind, but finds no conclusive evidence that it isn't a real person. (People can shield themselves from intrusion.)

First, Telzey tries tailing her, even having her airtaxi followed, but loses her in traffic. Her curiosity getting the better of her, she investigates Matridramas and finds the name of Wakote Ti, a local scientist and industrial tycoon. She meets with him and his assistant Lindsay, and inquire about the possibility of a runaway puppet. She learns more about how the Matri are created and programmed, and how the matridramas are written and acted out. After her visit, she decides to travel to see a drama elsewhere, instead of a local show, but she doesn't make it there.

Telzey wakes up in a room, wearing different clothes. Or maybe she woke up in a different room wearing the same clothes. She is confronted with a duplicate of herself, and both think that they are Telzey. They are informed by Wakote Ti, who kidnapped her, that one of them may be Telzey, and one or both may be puppets of Telzey. He made a duplicate, while suppressing her psi ability. Her ability will return in time, but this is an experiment to see if the psi ability will be duplicated as well. And if they can be controlled.

They are given freedom to move about the island complex. (Most of the island is inhabited by experiements that didn't work out well.) The two of them have not been programmed yet because he thinks that they will be useful or valuable as they are. In the meantime, based on a coin flip, he calls one Telzey and the other Galiel, the name of the puppet who was made into a copy.

Now the two must figure out who is who, and how to escape the island. There are complications when Ti's dead wife, Challis, returns. She is a puppet that the computer generates on its own every now and then. She doesn't last long, but she doesn't have a message from the computer to Telzey and her copy.

I enjoyed this this story, especially with some of its retro-future eccountrement. (It wasn't retro future then.) And if my original mandate was to find stories that could be made into anthology television episodes for streaming services, then this is a winner, right out of the gate. There is a story that can be shortened to an hour, albeit leaving out a lot, or lengthened to a six-part arc, if necessary. Just waking up and finding her duplicate screams "End of Episode 1". However, it would have to come much earlier if it was only a two-parter.

Overall, there aren't that many roles to fill. Telzey can be one actress in a dual role, or twin actresses dividing the workload. Ti and Lindsay are the bad guys. Challis, who can also be the runaway puppet early on. A handful of extras with speaking parts besides.

I'd watch it.

The Analytical Library: The poll score are shown for five stories in the September and Ocober 1970 issues. Oddly, the three lowest ranked stories are written by Gordon R. Dickson, Hal Clement, and Stanley Schmidt. Why this is notable is because those are the only 3 out of 10 whose names I've heard of. Clement and Dickson suffer from the fact that there stories were serialized, only being a last part, and the other the first of a new serial. In fact, the conculsion of Dickson's piece is in this issue. I'll likely skip that until I have time to read them all.

Short Story: "Homage" by Tak Hallus, with an illustration by Vincent di Fate, showing a man seated in a chair, a second standing facing away, and an oddly-drawn horse with a spiked tail. There is a moon or a planet in the night sky. The caption reads, Just because it was something any normal child learned did not mean a normal adult could do it!

Jacob had been brought by his parents from Earth to Xenos when he was a child. Now he is making a return visit. The trip has been problematic for him as he caught mumps, measles and chicken pox, in succession. Dr. Hurley has run tests and sends the results to Earth for analysis before Jacob can visit the grown sister who had stayed behind on Earth with her husband.

It turns out that Jacob has developed immunities to conditions on Earth, and that has affected his abilities to fight off the childhood illnesses of Earth. What will this do fir his visit?

On a scale of 1-5, I'd give it a 3.5., maybe a 4. Nothing wrong with it, but not much to it.

In terms of filming it, it would be simple, but it's lacking in the visual storytelling department. It all takes place in a couple of rooms on a ship, with exterior shots of the Moon and the Earth. The horse creature, a poison-tailed totenpferd, only appears in a fever-induced dream, and is basically a metaphor. If you are going to go to the trouble of including it, you'd need some flashbacks to Xenos. There are basically two speaking parts, and all they really do it speak. That's not to say a story couldn't be based on this on, or even on Xenos itself. With the horses.

Science Fact: "The Scientitific Gap In Law Enforcement", by James Vandiver. With the wide variety of fields of research covered by Analog's readers, some of you should be able to come up with useful answers to these real, here-and-now-problems.

There are three types of fingerprints, loosely grouped: visible, or contaminated prints, left by a hand or foot covered with paint, blood, dirt or the like; plastic prints, left in soft materials like putty, wax, butter, dust or dist; latents, which are invisible but the body oils and perspiration that make them can often been seen, especially on nonporus surfaces. For plastic prints, impressions can be made, usually with silicone or another casting material. Most crime scene prints are latent, which require processing before they can be photographed.

Making prints visible can be done with cigarette or cigar ashes or with commercial powders. Chemist's Gray is a mix of chalk and mercury. Also used are lampblack and aluminum dust. Dragon's blood is a brown resin from the rattan palm used in varnishes, and rosin is another. (Keep these in mind when writing fantasy.) Some 50 substances have been used, including types of carbon, talcs, kaolin, sulphur, gold and aluminum bronzes, powdered zinc, iron and platinum, feldspar, lead carbonate (on fruit skins), calcium sulphates, magnetic iron oxides, mercury salts, manganese and titanium dioxides.(At this point, I'm just copying large blocks of text, so I'll stop.)

Except to mention there are a few paragraphs about Xerox toner.

Something I didn't know. Some people don't have friction ridges, which are required for fingerprints.

The article goes into deatials about body oils which cause and can be detected in prints, and possibly developed different powders that turn different colors when detected. (I have no clue if any such thing has been developed in the past 50 years.) There's also the problem of different powders working better on different surfaces, and the fact that powders can danage the surfaces with the prints.

I read through the rest of it, but the talk of new types of brushes and development of new brushes was not anything of interest to me, particularly when realizes how out of date it all is.

Short Story: "The Enemy" by M. R. Anver, with an illustration by David Cook, showing two men fighting with fists, as a third man with a filter mask and some kind of snub pistol flees. Below the title is a furry, six-legged beaked creature with eyestalks. The caption reads, The greatest danger from aliens is that we haven't evolved with them -- and haven't evolved defenses against their special attack methods!

In the years after a conflict, a Cadosian is working with Terran scientists at a Comsearch station on Signa II. Comsearch is a private firm because government resources are stretched too thin already. The Cadosian, Faon, wakes up in pain. The research station has been attacked, with localized damage, and everyone inside is dead, except for him and George, an autochthonous species, conventional endotherm. The humans adopted it as a mascot. Faon doesn't remember what happened.

He is rescued by two Terrans, named Evans and Jel'Shtein, who are a bit wary of the alien and former enemy of Earth.

Now they want to investigate the mystery into all the deaths. Was it an infection? If so, it could spread with them to other planets? Was it an attack from above? The damage is too local and minimal. So what could have happened?

In the end, Faon figures out the caused of the madness that caused the researchers to kill each other (as hinted at in the illustration).

As for as dramatization goes, you need 3 actors (or actresses), and a number of extras. The animal could be a trained cat with CGI overlaid, or purely CGI. I'll leave that for smarter minds that me. The theme of mistrust of aliens along with the murder mystery is perfect for an episode of a TV anthology series.

Serial: "Tbe Tactics of Mistake" by Gordon R. Dickson, conclusion. Illustrated by Kelly Freas

I'm skipping this to read at a later time. I haven't read any Dickson in quite a while, but I remember enjoying what I did read, and that was back at a time when I wasn't reading a lot of books at all.

Novelette: "Sprog", by Jack Wodhams, with an illustration by Leo Summers of a guy sitting in front of a 60s-style computer (complete with reel tape), getting a printout. There's an older man behind him in what appears to be a tweed or checkered jacket. To the side is a man dressed like a driver. On the facing page, there's a horse race. (Two horse stories!) The caption reads: It wouldn't make a bit of difference what method was used, as long as it worked. But, of course, if it worked, it would have to be useless...

The strat of this story reminded me of when editors say "the story just didn't grab me" because this one didn't. But I stuck with it. Johan Schmidt was trying to cash in on his invention, which he overworked for precision, but no one is interested. He can't even demonstrate it for free, and even when he pays for marketing, few are interested. Or worse, the wrong people. Apparently, it was not geared toward the population of youthful and older women he was attracting. And they found it disgraceful.

What was disgraceful? Well, I didn't rightly know. Wodhams appeared to be talking in circles and generalities. There's a bit of technobabble with the Assistant to the Assistant to the Secretary to the Minister of Industry about the sensory instruments and their infallibilty for projections. The government lackey comes to believe that Schmidt has a crystal ball to sell, and sends him on is way.

Schmidt decides to try the Defense Ministry next, and after showing up day after day, first thing in the morning and waiting until nighttime, they finally give him an audience so he'll go away. This is when we find that he read information about people and can determine things that will happen months from now. A senior clerk listens to Schmidt's description and sums up the paradox of his machine.

Similar to some Twilight Zone episodes, it's a device that can predict the future, but knowing that the future can be predicted can affect that future. The clerk realizes that if he tells them something will happen in six months, either they can take steps to prevent it, and therefore there would be no way to prove the device's effectiveness, or they would be helpless to prevent it, in which case the device would still be useless to them. Being forewarned is not the advantage it seems to be.

From here, Schmidt is approached by an enemy agent named Tuic, who has noticed his long daily visits to the Defense Ministry. He takes an interest in SPROG, the Scientific Prognosticator. He reveals information about himself to get a reading, and Schmidt details things that happened to Tuic in his past. When he tries to predict what will happen next Monday, the machine is blank. Friday is blank as well. Tuic is going to die. He leaves Schmidt and his machine, and is run down by car, and dies.

The car is driven by a man named Gimmidge who works for Sir George Poncefoot. Sir Geroge takes an interest in Schmidt's prediction, and has him figure out Gimmidge's future. He will come into money, move away and live a long life. (Gimmidge is displeased to know the age at which he'll die.) Sir George wants to know about the happiness he'll experience only for the coming weekend. He finds out that no joy is coming. And when he loses every bet on every horse that Saturday, he starts to believe in Schmidt.

He then comes up with a plan to have ten workers place bets so he can find out which will experience moments of happiness. But the readings don't seem to make sense. Or do they?

This is a long entry for a long story that I initially wasn't too interested in, but I made it through. Granted, had I read it in the 70s or 80s, I might have likely given up.

Could this be made? Maybe, but I would condense it greatly. The audience is pretty savvy to the paradox involved, so that scene could be simplified. In fact, the first third of the story should likely be only a few minutes of time. You would need Schmidt, a couple of clerks or ministers, the spy, Sir George and Gimmidge. Lots of extras would be needed for the assistants and the crowds at the race track. It's workable. The prediction paradox has been done before, but this time, it has horses. This has a nice twist in the end, and a good resoltuion for Schmidt.

The Reference Library , by P. Schuyler Miller. Yes, I read through the book reviews for books that came out in 1970, even though I probably will never see these books, even the ones by Andre Norton, Poul Anderson, or Michael Moorcock. There was also a long introduction to a survey for the best short science fiction, both new and old (with some overlap). I am curious as to how that all worked out. Maybe in a future issue.

Brass Tacks: The letters to the editor were intersting because it started off with a response to the editorial "Cliff-Hanger" which was written in response to Apollo 13. I might have to look that one up. This was followed by letters about fertilizer runoff (there isn't), a wife of an engineer who discovered science fiction while looking for new things to read, and this amusing bit:

"It's almost amusing to hear pseudo-Liberal politicians in government and elsewhere describe themselves as the saviors of humanity and their enemies as Facists. For years, in their political campaigns, they've denounced their opponents ..."

Some things never change.

And there was something about biological warfare.

I missed all that stuff, but you have to start reading somewhere.

On to February, as soon as I finish another book I've been reading away from the PC.

No comments:

Post a Comment